The game is on: increased competition law scrutiny and enforcement in gaming industry

The past years have seen video games surge in popularity. Although the growing popularity of video games may have partly arisen from the lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, the growing popularity of video games is set to continue in the near future as over half of the world’s population is expected to be gaming in 2024. The increasing popularity of video games is reflected by increasing valuations of the gaming industry. Whereas the gaming industry was already valued at approximately € 160 billion in 2021, its value is expected to grow to almost € 300 billion by 2027. A significant part of this growth is propelled by the growing popularity of mobile games, as almost everyone now has access to video games through their smartphone.

The rapid growth of the market for video games has not only yielded new technological developments and a wider range of video games but also brought along increased public and private enforcement of competition law. This blog provides an overview of the relevant players on the gaming market as well as the most significant developments of competition law enforcement in the industry.

Players on the market

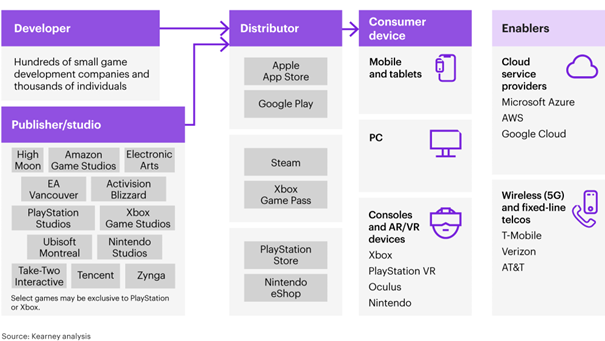

The gaming industry can be subdivided into (i) PC games, (ii) console games, and (iii) mobile games. Within these markets, different market players contribute to bringing a game to the player.

A game is developed by a developer who is responsible for all the aspects integral to game development, such as the software and overall design. Once completed, a game is published by publisher. These publishers typically finances the development process and invests in the marketing of the game. It is, however, also possible for developers to market their games independently. Supergiant Games, for example, is responsible for both the development and the publishing of their video games.

The European Commission considers the market for developing and publishing PC and console games to be distinct from developing and publishing mobile games. The European Commission has left open whether or not this should be further segmented, for instance by distinguishing separate consoles (such as the PlayStation (Sony), the Xbox (Microsoft), and the Switch (Nintendo)) because of potential single-homing thereof, meaning that a user only uses a single console.

Users ultimately access a game through the game distributor. This can be a physical shop but is increasingly a digital platform. Well-known examples are – depending on the device of choice of the user (PC, console, and/or mobile phone) – Steam, Microsoft Store, Epic Games Store or the Apple App Store. Through these platforms, a game can be bought and/or downloaded. The market for game distribution can also be distinguished between (i) PC and console games and (ii) mobile games. The (adjacent) market for operating systems is often also relevant. In that regard, markets for operating systems of PCs (e.g. Windows, servers (e.g. Linux), and mobile devices (e.g. Android) can be distinguished.

Some large gaming companies are vertically integrated: they operate at multiple levels of the distribution chain – from developing and publishing to distributing games. For example, Microsoft operates as a developer (e.g. through subsidiary Obsidian Entertainment), a publisher (through Xbox Game Studios) and a distributor (through Microsoft Store) and has its own PC operating system (Windows). In addition, Microsoft also has its own console, the Xbox. Another example of a vertically integrated company is Sony, which is the producer of the PlayStation and owns multiple game developers (such as Insomniac Games), and also publishes its games through Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Monitoring acquisitions in the gaming world

This vertical integration of companies like Microsoft and Sony is partly due to major acquisitions, such as Microsoft’s takeover of Activision Blizzard (known for Call of Duty), Take-Two Interactive’s acquisition of Zynga (known for FarmVille) and Sony’s takeover of Bungie (known for Hal0).

This has, consequently, led to a significant increase in the number of merger control notifications to the European Commission. Since 2010, the number of merger notifications filed before the European Commission regarding the gaming industry has tripled. The competitive landscape in the gaming industry has also changed over the years. Until recently, acquisitions in the gaming industry were typically not considered to lead to anti-competitive effects. This was mainly due to the large number of game developers and distributors active in the market as well as the wide variety of games on offer, which makes the gaming market diverse and dynamic.

For instance, the European Commission approved Activision Blizzard’s acquisition of King in 2016 on the grounds that there were enough sufficient competitors in the video game market to ensure competition. Activision Blizzard itself was already the result of an acquisition by which the Vivendi Group, the parent company of Blizzard, acquired Activision. The European Commission approved this acquisition unconditionally.

Competition authorities have become increasingly critical of acquisitions in the gaming industry in recent years. This is due to the increased degree of concentration in various markets and the (further) vertical integration of gaming companies, which generally increases the risks of anti-competitive effects. For example, in 2021, the European Commission approved Microsoft’s acquisition of game developer and publisher Zenimax only after a second-phase investigation. The investigation was deemed necessary to determine with certainty that the parties involved could not adopt exclusionary strategies.

The most high-profile acquisition in recent years is undoubtedly the one of Activision Blizzard by Microsoft. Activision Blizzard is the developer and publisher of popular games such as ‘Call of Duty’, ‘Guitar Hero’, and ‘World of Warcraft’. The European Commission also launched a second-phase investigation into this acquisition. Only after this in-depth investigation, the merger was approved conditionally.

The European Commission’s concerns with this acquisition also related to ‘cloud gaming’, a recent development in the gaming industry. In cloud gaming, games are streamed from a server (‘cloud’) which can then be played on any kind of device, from mobile devices to PCs and consoles. Although cloud gaming currently only accounts for 1% of the global video game sales, it is considered the future of gaming. Microsoft already operates a cloud gaming service through its ‘Xbox Cloud’ but it is certainly not the only one: US-Based Nvidia developed Geforce Now, Amazon offers its cloud gaming service ‘Luna’, and Sony recently launched its own cloud gaming service through PlayStation Plus.

The barriers to entry for cloud gaming services are, however, rather high. Sony’s CEO, Kenichiro Yoshida, stresses: “I think cloud itself is an amazing business model, but when it comes to games, the technical difficulties are high”. Not every attempt to enter the market is therefore equally successful, as evidenced by Google’s discontinuation of its own cloud gaming service ‘Stadia’ as of January 2023.

The European Commission feared that after the acquisition, Microsoft would make Activision Blizzard’s games exclusively available on Xbox Cloud, thereby putting rival cloud gaming services at a significant disadvantage to Microsoft already at an early stage. To remedy these concerns, Microsoft pledged to (i) grant users a licence to access Microsoft’s Activision Blizzard games on any cloud gaming service – not just Microsoft’s – for the next 10 years, and to (ii) for the same period, grant a corresponding licence to all cloud gaming service providers so that they can make these games available to users. By doing so, Microsoft commits to not make Activision Blizzard’s games exclusively available on its own Xbox Cloud gaming service, thus allaying the European Commission’s concerns.

Remarkably, the UK’s competition authority, the Competition & Markets Authority (“CMA”), deemed these commitments insufficient and prohibited the acquisition in April 2023. Like the European Commission, the CMA also foresaw a “substantial lessening of competition” in the cloud gaming services market as a result of the acquisition, despite Microsoft proposing the same behavioural remedies as it did to the European Commission. However, the CMA considered these remedies to be insufficient, partly because they would be difficult to monitor and because they would still allow for games to be played only via the Microsoft Windows operating system.

In August 2023, to alleviate the CMA’s concerns, Microsoft decided to sell the streaming rights for Activision Blizzard’s current and future games (for the next 15 years) to Ubisoft. This makes Activision Blizzard’s games streamable on Ubisoft’s services and further leaves it up to Ubisoft to whom it further licenses these streaming rights anywhere outside the EU. Microsoft then filed a new notification of the acquisition to the CMA. After this commitment, the CMA finally approved Microsoft’s acquisition of Activision Blizzard.

In the United States, Microsoft has also been allowed to proceed with its acquisition of Activision Blizzard, despite the US Federal Trade Commission’s (“FTC”) initial prohibition to implement the acquisition of December 2022. The FTC ’s refusal was subsequently overruled by a US court, which held that Microsoft was allowed to “close” the deal, after which the FTC cut its losses. With the acquisition of Activision Blizzard being fully completed in the US, the EU, and the UK, Microsoft now is the third-largest gaming company in the world, behind only Tencent and Sony.

Behavioural oversight by authorities as well as competitors and users

Besides (ex ante) merger and acquisition supervision, the European Commission has also not been idle in terms of (ex post) enforcement of competition law in the gaming industry. For instance, Valve – the company that operates the video game platform Steam – and five game developers (Bandai Namco, Capcom, Focus Home, Koch Media, and Zeniax) were fined a total of almost € 8 million for engaging in geo-blocking in 2021. Valve granted activation keys to these game developers that allowed games not bought through Steam to still be played on Steam. At the request of the developers, these activation keys contained a geographical location restriction, which meant that the key could only be used in the Member State where the game was purchased. This way, Valve and the developers sought to prevent users from purchasing games at a lower price in one Member State and then playing them in another (i.e., their own) Member State where the same game(s) are sold at a higher price. Valve argued in its appeal against the fine that this was intended to protect developers’ copyrights and that it also has positive effects on competition. However, this appeal was declared unfounded by the General Court in September 2023.

Private enforcement in the gaming industry is also on the rise. For instance, Epic Games Store – known for Fortnite – started proceedings in the US against Apple over the 30% commission Apple charges for in-app purchases and the obligation to use Apple’s payment system. Epic has recently initiated a similar claim against Google with regard to the Google Play Store.

A similar case is also being pursued in the Netherlands, where three foundations filed class action suits against Apple. The foundations accuse Apple of violating Articles 101 and 102 TFEU because of the high commission rates for paid apps and in-app purchases in the Apple App Store and the fact that these payments could only be made through Apple’s payment system. In this context, the foundations partly base their claim on a recent decision by the Authority Consumer & Market (“ACM”). The Dutch regulator deemed it unfair that dating app customers could only make in-app purchases through the payment method imposed by Apple. The ACM forced Apple to amend its unfair terms, which the tech giant eventually did after forfeiting €50 million in penalties. Although this decision by the ACM does not directly affect the gaming industry, it does seem to have prompted the filing of class actions by these foundations.

These cases illustrate that private enforcement of competition law in the gaming market is also on the rise. Given the many developments and increased degree of supervision on this market, it is only a matter of time until more such (follow-on) cases begin to emerge.

Conclusion

Developments in the gaming world are increasing at a rapid pace and the growing popularity of video games does not seem to slow down. These developments are not going unnoticed by regulators either. The increase in the number of acquisitions as well as their value – and the impact this has on the competitive playing field – have already caused tighter merger supervision in recent years. Additionally, public and private enforcement of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU is increasing. All in all, the gaming market will continue to develop, and with it the enforcement of competition law on it.