DMA-obligations come into force; a bird’s-eye view of the (technical) changes by the designated gatekeepers

Compliance Day; as of today, all gatekeepers designated by the European Commission (“Commission”) must comply with the provisions of the Digital Markets Act (“DMA”). In the run-up to this deadline, gatekeepers have been aligning their core platform services (“CPS”) with the provisions of the DMA. At the time of drafting, Apple and Meta have published their compliance reports. It is expected that more will follow in the course of today.

In addition to the adjustments required to comply with the DMA, there have been other interesting developments. In our previous blog, we already touched upon the appeals brought by Apple, Meta, and ByteDance against the designation of one or more of their services as CPS. Meanwhile, the Commission has alsop decided not to designate certain CPS, and new gatekeepers have reported themselves to the Commission.

This blog provides an overview of the recent developments and the adjustments that gatekeepers will introduce or have already introduced to comply with the obligations under the DMA.

- Overview of general substantive obligations for gatekeepers

- Alphabet

- Amazon

- Apple

- ByteDance

- Meta

- Microsoft

- Possible new gatekeepers and CPS: Booking.com, X and ByteDance

Overview of general substantive obligations for gatekeepers

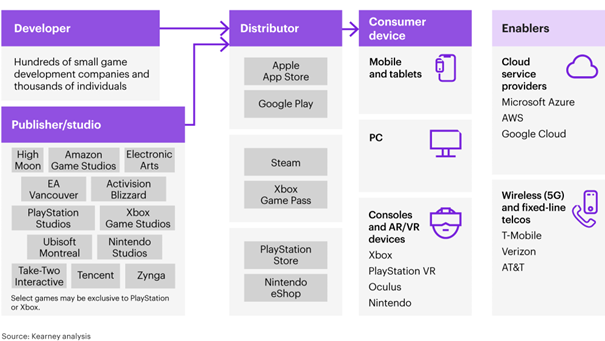

On 6 September 2023, the Commission designated the following gatekeepers and CPS:

source: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/nl/qanda_20_2349

Some obligations stemming from the DMA are only relevant to a particular CPS. For example, the interoperability of number-independent interpersonal communication services is relevant to WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, but not to Chrome or iOS. However, a number of obligations from the DMA apply to, and are relevant to, any kind of CPS and/or concern the interrelationship between (the use of) different CPS. The following provisions are particularly noteworthy in that context.

- Article 5(2) DMA generally prohibits gatekeepers from combining personal data obtained from various (core platform) services without the end-user’s consent. Gatekeepers must thus obtain prior consent to combine and use personal data from different services in order to personalise ads and content. On the basis of Article 15 DMA, gatekeepers should furthermore provide a yearly audited description of any techniques for profiling of consumers that they apply (see for example Meta’s first report here).

- Pursuant to Article 5(4) DMA, gatekeepers are required to allow business users to make offers (free of charge) to end-users acquired through the CPS or through other channels, and to conclude contracts with those end-users. Put differently, a gatekeeper may no longer prohibit business users from contracting or making offers for their services to end-users outside of the CPS. Also, the gatekeeper must – in accordance with Article 5(5) DMA – allow end-users to access and use certain services, content, subscriptions, features or other items through its CPS, even though the enduser acquired such access from the relevant business user directly (outside the CPS).

- Article 5(8) DMA provides that gatekeepers may not require users to subscribe to or register with other CPSs as a condition for using or accessing a CPS of that gatekeeper (such as tying and/or bundling practices).

- For consumers (end-users), Article 6(9) DMA is particularly relevant. Under this article, gatekeepers must allow end-users (upon request) to transfer the data they have provided or generated, and end-users must be given continuous real-time access to that data (data portability). The equivalent of this data portability obligation towards business users is contained in Article 6(10) DMA.

- Finally, in general, under Article 6(6) DMA, gatekeepers may not impose technical or other restrictions on end-users switching to other software applications and services accessed through the gatekeeper’s CPSs. In the same light, under Article 6(13) DMA, gatekeepers may not impose disproportionate general conditions for terminating the provision of a CPS. Moreover, these termination conditions must be exercisable without undue difficulty.

As these obligations apply in any case, they are not in principle elaborated in the overview below. However, the relevant provisions of the DMA are discussed when the gatekeeper has explicitly proposed adjustments to meet these obligations.

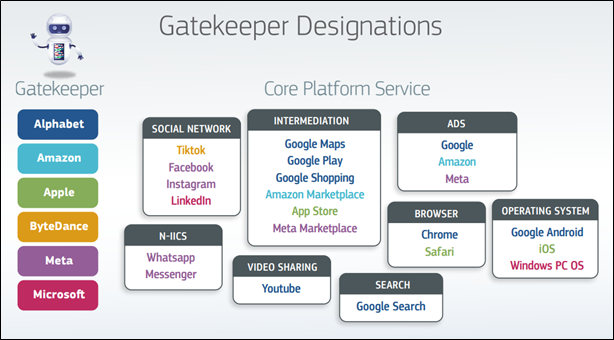

Alphabet

Alphabet is the gatekeeper with the most CPS. As a result, there are many changes that need to be implemented to comply with the DMA.

To comply with Article 5(2) DMA, Alphabet will now let end-users decide whether to keep all CPS linked. If the CPS are linked, end-user personal data can be exchanged. In addition, a “consent or pay” option – where consumers consent to the use and combining of their personal data or pay a (monthly) fee to use the CPS – is still under discussion with the Commission.

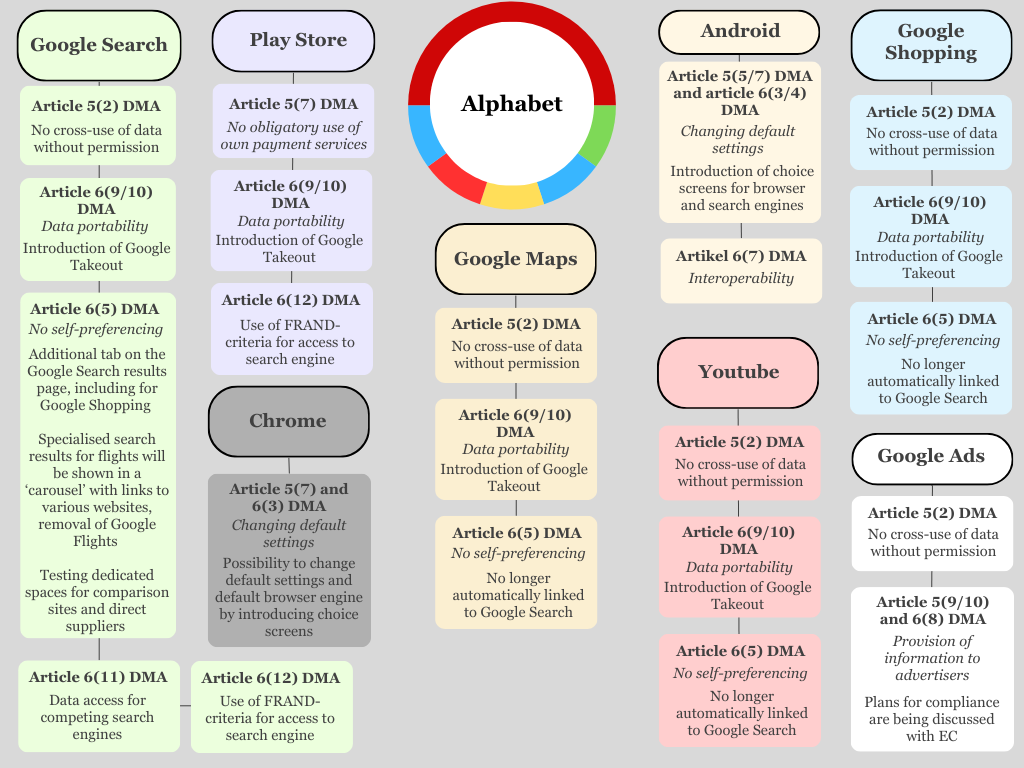

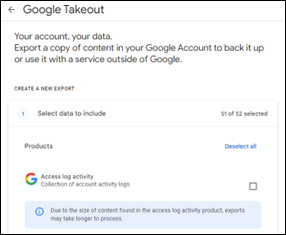

In light of Article 6(9) DMA, regarding data portability, Alphabet has already been using Google Takeout for a while now. This tool allows users to download or transfer their data to another platform free of charge. To bring this process in line with the provisions of the DMA, Alphabet will soon test a new API (‘Application Programming Interface’) to facilitate the download and transfer of data. Alphabet has also announced to launch a data portability software in Europe this week, making it easier for developers to move user data to a third-party app or service.

Another significant change for Alphabet is the effect of Article 6(5) DMA, which in short prohibits self-promotion in rankings and requires the gatekeeper to use transparent, fair and non-discriminatory terms for those rankings. For Alphabet, this particularly affects the CPS Google Search, Google Maps, Google Shopping, and Youtube. For Google Shopping, Google Maps, and Youtube, Alphabet has announced that these services will henceforth no longer be linked to Google Search’s search results page by default. However, end-users can choose to link (one of) these services to (the search results of) Google Search by default.

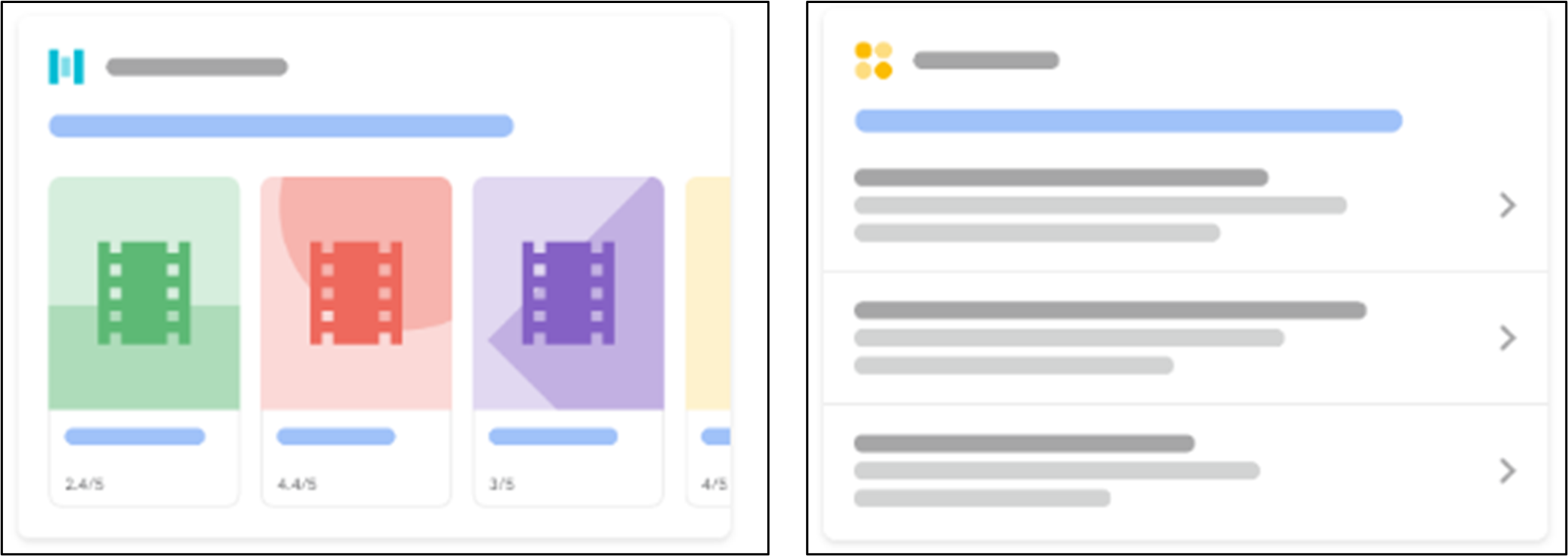

As for Google Search itself, Alphabet says it is adding a tab to the search screen. This will not only allow users to filter by things like videos and images, but also by comparison services. In addition, Alphabet will remove its own specialised results window for flight searches (see below).

Instead, a carousel is displayed showing links to various comparison websites. Alphabet has shared the following possible examples.

For categories like hotels, Alphabet is starting to test a dedicated space for comparison sites as well as direct suppliers to display more detailed results, including images and reviews.

With regard to Alphabet’s advertising service, the tech giant’s most lucrative (core platform) service, Alphabet is required under Articles 5(9), 5(10) and 6(8) DMA to provide certain data to advertisers when they request it. The announced compliance plans for this are still being coordinated with the Commission.

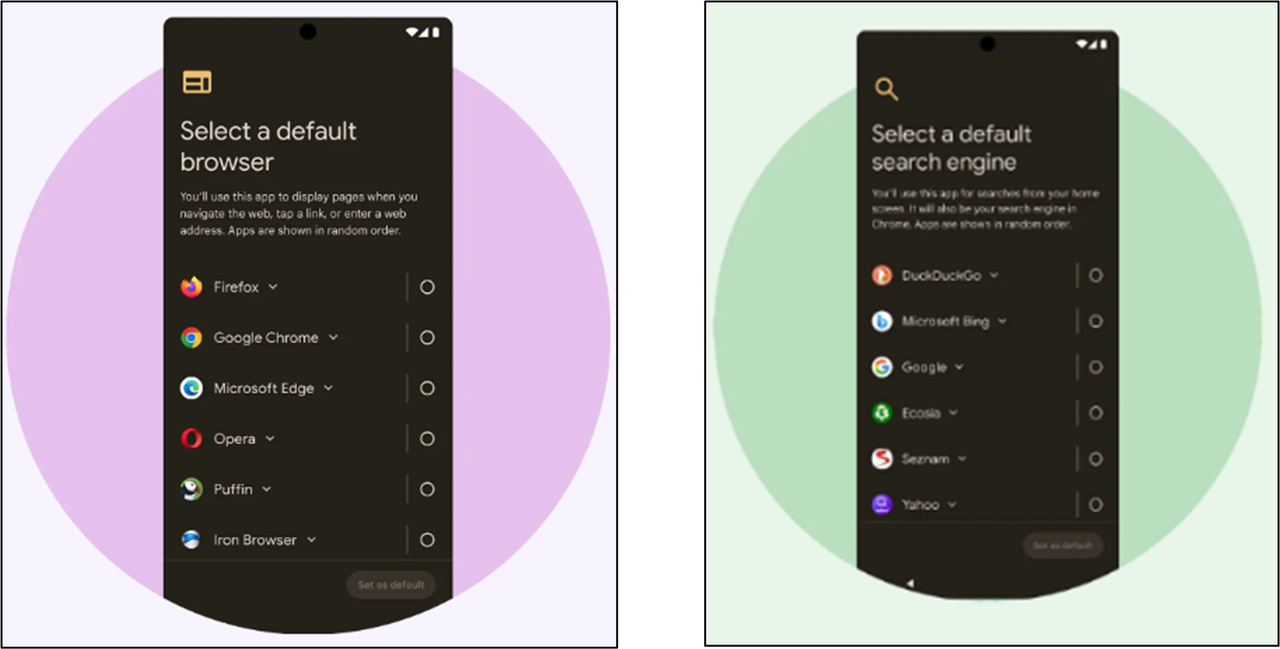

For Google Android and Google Chrome end-users should be allowed to change their default settings pursuant to Article 6(3). End-users should also be allowed to switch browsers under Article 5(7) DMA. Alphabet has indicated that it will add a choice screen for the default search engine and browser during the initial setup of a device using Alphabet’s CPS, as illustrated below.

Finally, Alphabet must now also allow end-users to use other app stores under Article 6(4) DMA. As regards its Play Store, Alphabet has announced that app developers will be able to use alternative payment methods.

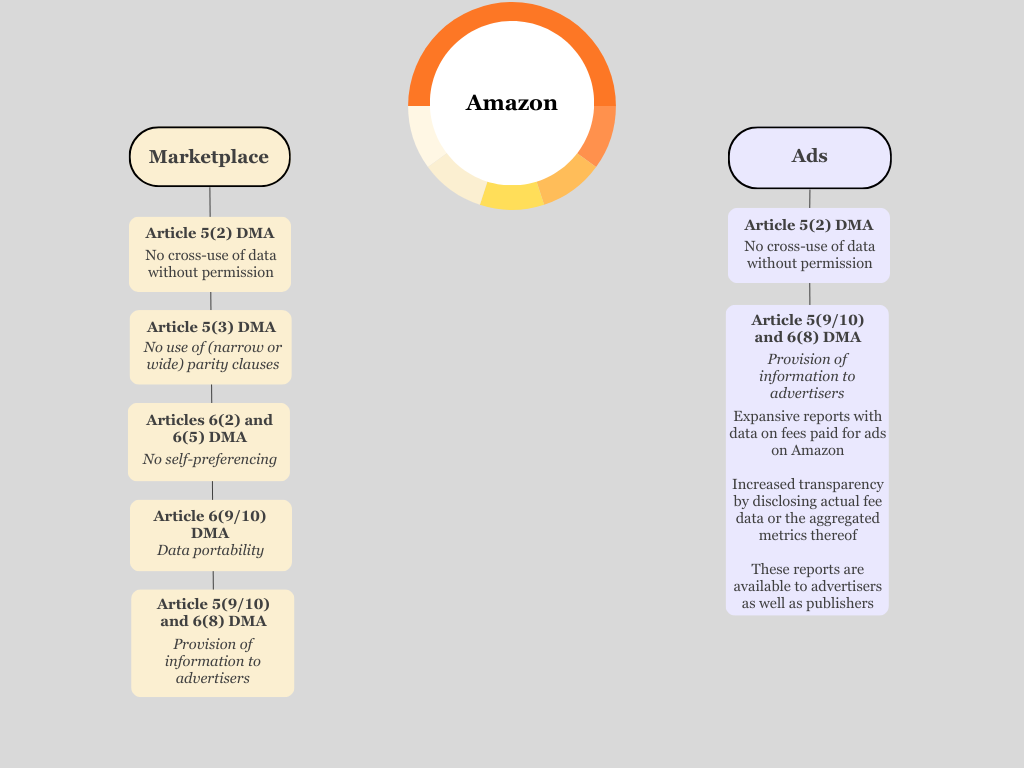

Amazon

Like Alphabet, Amazon also has a lucrative advertising service. Thus, Amazon too has to provide certain data to advertisers upon request under Articles 5(9), 5(10), and 6(8) DMA. Amazon has indicated that from 7 March 2024, it will provide comprehensive reports detailing ad costs paid by advertisers and received by publishers, displayed on third-party websites and applications. According to Amazon, these reports provide insight into the financial transactions between advertisers and publishers. The reports can be accessed by advertisers through the ‘Amazon Ads dashboard’, and by publishers through the ‘Amazon Publisher Services portal’. In doing so, advertisers and publishers can choose whether to disclose their cost data, or whether the data will be included in standard aggregated metrics. This flexibility allows users to adjust the level of transparency based on their preferences and business needs, Amazon said.

Amazon’s main obligation with regard to its best-know service, Amazon Marketplace, can be found in Article 6(2) DMA. This article prohibits the gatekeeper from using non-public data generated by competing business users for its own CPS. Article 6(5) DMA furthermore contains a prohibition on self-preferencing relating to the ranking of competing products and services on the gatekeeper’s platform. These provisions reflect the Commission’s 2022 investigation into Amazon’s Buy Box and Prime Programme. The investigation was eventually concluded through commitments.

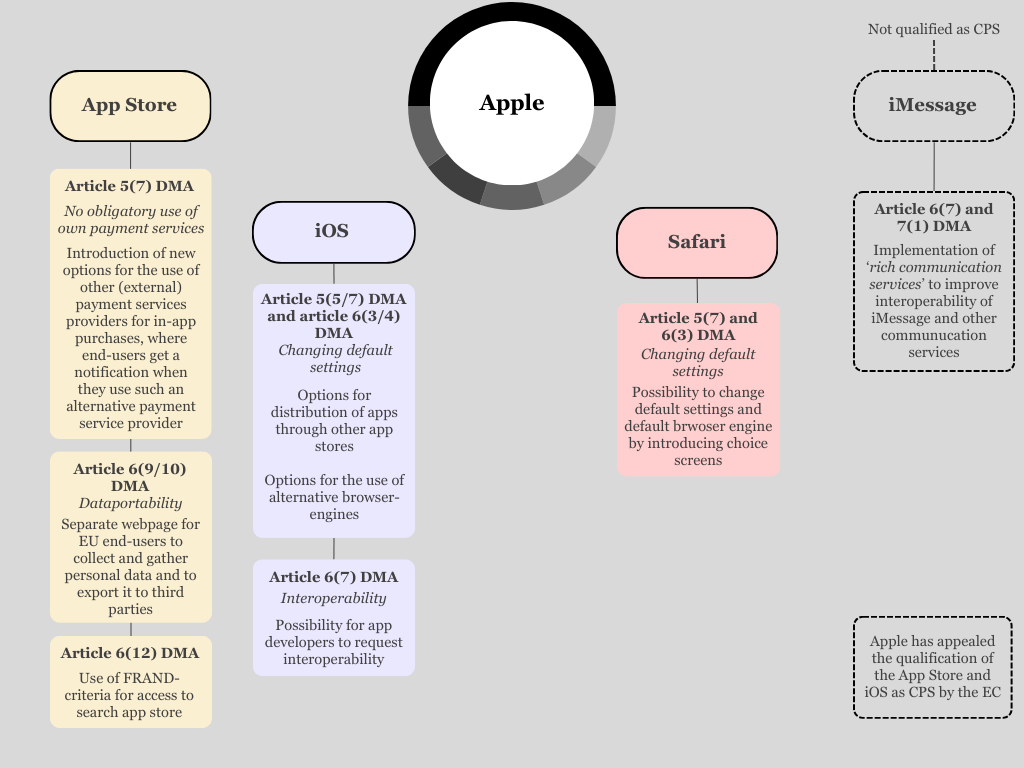

Apple

Apple appealed its gatekeeper designation, as well as the App Store’s qualification as a CPS, on 16 November 2023. Nonetheless, Apple must comply with its obligations under the DMA as of today. It has therefore announced the following changes for its CPS. These will be briefly discussed below. In addition, Apple has published its first compliance report on 7 March. In this document, it sets out the specific obligations and (proposed) changes in more detail.

The App Store brings consumers and app developers together. For developers, the following will change. They will have options to use (other) payment services to finalise in-app purchases. Until now, Apple only enabled app developers to use its own payment system. In 2021, the ACM already imposed an order subject to a penalty payment on Apple for the mandatory use of its own in-app payment system for dating app providers. Apple eventually incurred the maximum amount of € 50 million in penalty payments. In accordance with Article 5(7) DMA, there will also be new options for processing payments via referrals: end-users can then complete a transaction for digital goods or services on the developer’s external website. There is still an ongoing discussion on the (other) conditions Apple imposes for the use of the App Store. For example, Apple envisages to maintain the ‘Core Technology Fee’ it charges to app developers in order to make use of the App Store.

These features are accompanied by a number of other changes. For example, Apple is introducing labels on the App Store product page that inform users when an app uses an alternative payment processing method (compared to Apple’s). There will also be so-called in-app ‘disclosure sheets’, which alert users when they are no longer making transactions through Apple, but using an alternative payment service. In addition, Apple is coming up with new processes to check whether developers accurately communicate information to end-users about transactions using alternative payment services. These changes are being introduced to protect consumers, Apple said.

Regarding the iOS operating system, Apple has indicated that new options are coming for distributing iOS apps through alternative app marketplaces. It will also become possible, using a new framework and new APIs, to develop alternative app stores and/or browser engines for iOS. Previously, only WebKit, the browser engine behind Apple’s Safari, could be used.

As for Safari itself, Apple is introducing a new selection screen that appears when users first open Safari in iOS 17.4 or later. On that screen, EU users are asked to choose a default browser from a list of options. It allows end-users to change their default settings and switch browsers (Articles 5(7) and 6(3) DMA).

All these CPS will also come with the ability to transfer/retrieve data, in line with Article 6(9) DMA. For instance, end-users will be able to retrieve and export new data on their use of the App Store to an authorised third party on Apple’s Data & Privacy site. App developers can use a form to submit requests for interoperability with iPhone and iOS hardware and software features.

Finally, Apple has indicated that it is introducing a number of adjustments in relation to iMessage, even though Apple’s service has not been designated as a CPS following a Commission investigation. Apple has pledged to improve iMessage’s interoperability with other communication services by implementing an RCS (‘rich communication services’) system. RCS includes features such as read receipts and type indication, which are already used with, for instance, WhatsApp. Green messages (messages between Apple and Android, for example) will also get these functionalities. Blue messages are those between devices of iOS users.

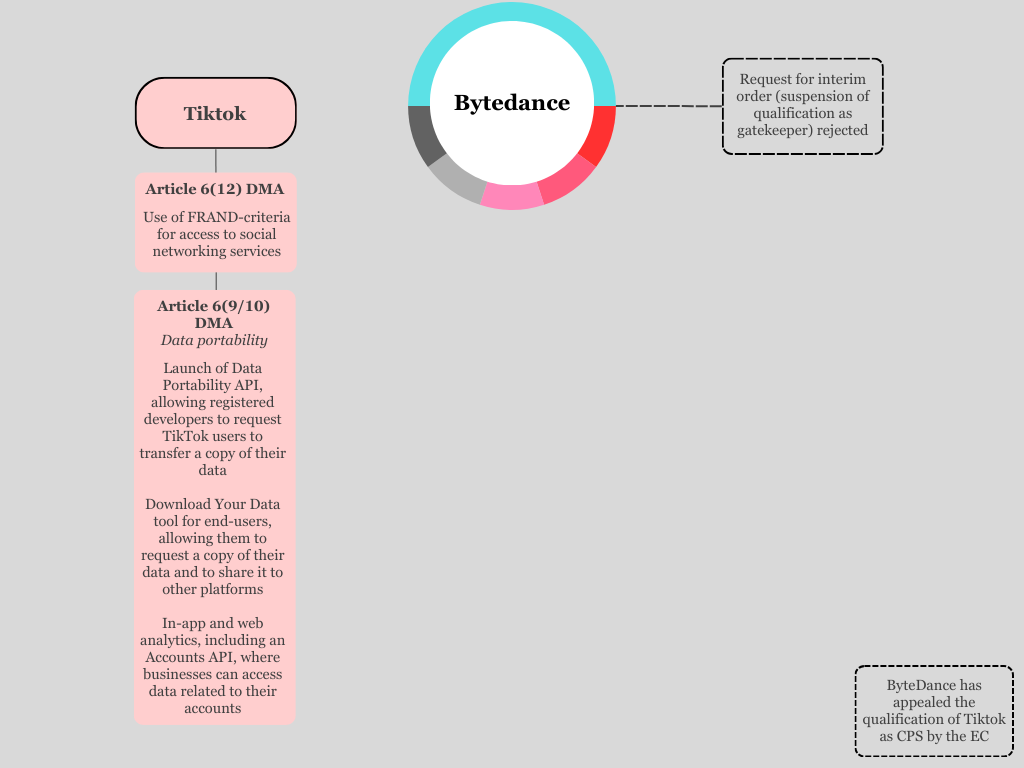

ByteDance

ByteDance, the company behind social network TikTok, unsuccessfully sought an interim injunction to suspend its designation as gatekeeper. In short, the President of the European General Court ruled in his order that ByteDance had not claimed, let alone demonstrated, that the alleged financial damage was serious and irreparable. This lacks the urgency required for an injunctive relief.

Thus, ByteDance too has to comply with the DMA’s obligations from today onwards. On 4 March, ByteDance published several changes on its website relating to the DMA. With TikTok’s ‘Download Your Data’ tool, end-users can request a copy of their TikTok data for access and portability purposes. TikTok has also launched a new ‘Data Portability API’, which allows registered developers to request end-users permission to transfer a copy of their TikTok data. End-users can allow for either a one-time or recurring transfer, and will be able to select specific categories of data or their full archive. TikTok also offers certain in-app and web analytics allowing business accounts to measure their performance. This includes an ‘Accounts API’ where businesses can access data related to their TikTok accounts.

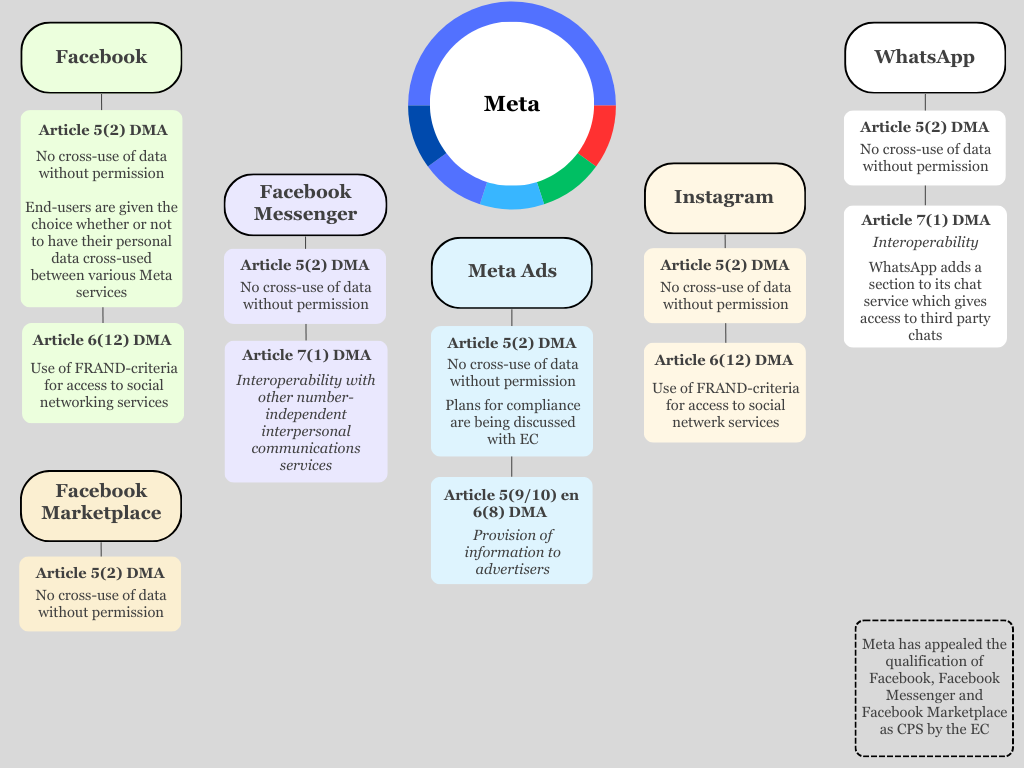

Meta

Meta has also appealed the qualification of some of its services as CPS on 15 November 2023. For instance, Meta disagrees with the Commission that Facebook, Facebook Messenger and Facebook Marketplace qualify as CPS. Nevertheless, in the meantime, Meta must comply with its obligations under the DMA.

Meta shows its proposed changes on its website. On 6 March 2023, Meta has furthermore published its first consumer profiling report and compliance report in which it further explains and illustrates the changes, mostly applicable as of today.

First of all, with regard to all of Meta’s CPS, it is not allowed to combine personal data from different (core platform) services without end-user consent (Article 5(2) DMA). Therefore, Meta now gives its end-users the choice to exchange data between Meta’s different (core platform) services. For example, end-users who have already chosen to link their Instagram and Facebook accounts can now choose to keep their accounts connected via the ‘Accounts Centre’, so that their information is used between their Instagram and Facebook accounts, or to manage their Instagram and Facebook accounts separately, so that their information is no longer exchanged. The same goes for Facebook Marketplace, for example. The compliance report contains specific examples.

With regard to Facebook and Instagram, end-users also have the option to use these social networks for free with ads, or to subscribe for a fee to stop seeing ads. If people subscribe to stop seeing ads, their information will not (no longer) be used for ads. This had previously been introduced by Meta as a result of the Digital Services Act coming into force. Although under the Digital Services Act, the Commission has now sent a formal information request to Meta in response to these ad-free subscriptions.

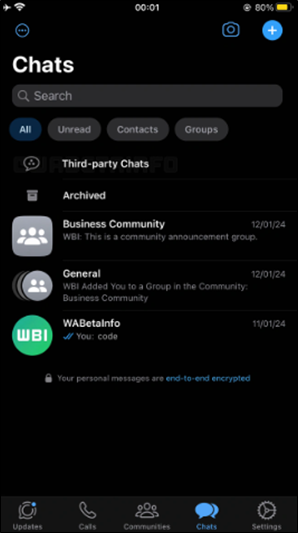

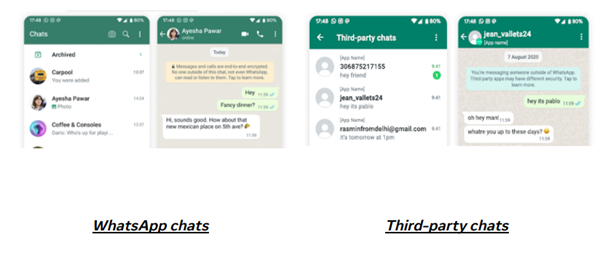

For WhatsApp, Article 7(1) DMA is particularly relevant. This article requires interoperability between number-independent interpersonal communication services. That means, simply put, that end-users should be able to chat with each other on for example WhatsApp via Facebook Messenger, or Apple’s iMessage, discussed above. Meta has requested the Commission for a six-month extension to the obligation to make WhatsApp interoperable.

To comply with this, Meta envisages to add a section to WhatsApp’s messaging service. If the end-user goes to this section, they will arrive at third-party chat services. WhatsApp is now testing this feature on iOS and Android. The examples below show what this could look like.

Meta has not yet announced any concrete changes on Facebook Messenger’s interoperability with other number-independent interpersonal communication services.

Finally, in relation to its advertising services, Meta Ads, Meta is required to provide data to advertisers under Articles 5(9), 5(10), and 6(8) DMA. Meta’s compliance report contains the first suggestions in that regard.

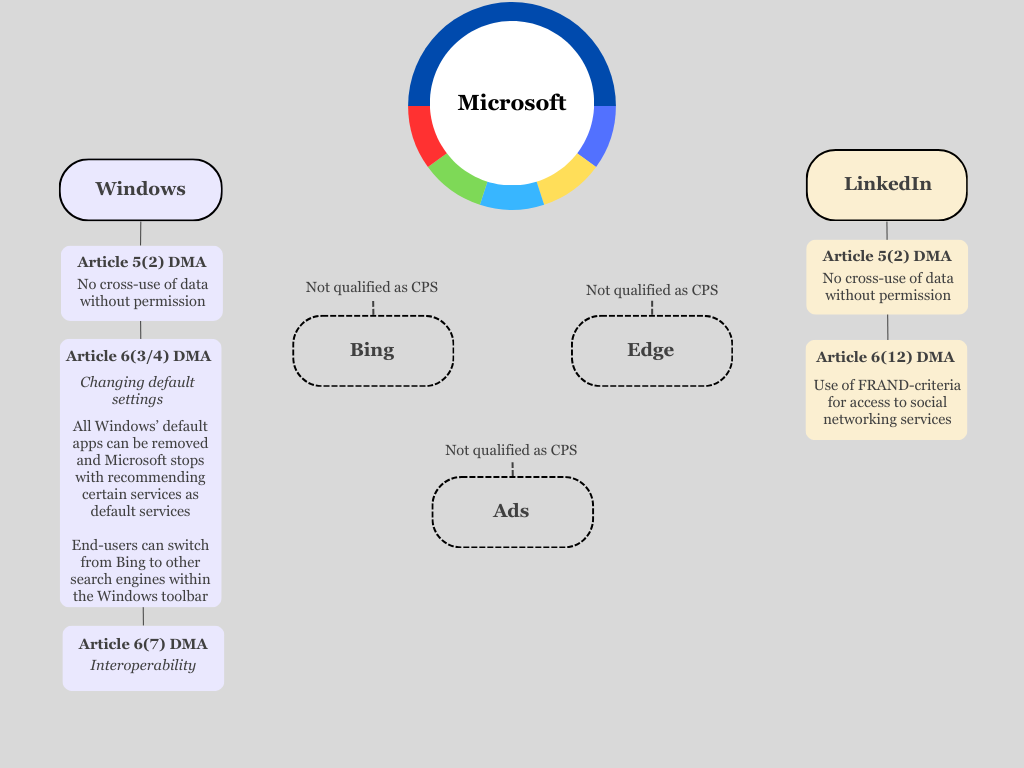

Microsoft

Microsoft has displayed and explained all its planned changes for Windows on its website and in a separate blog post.

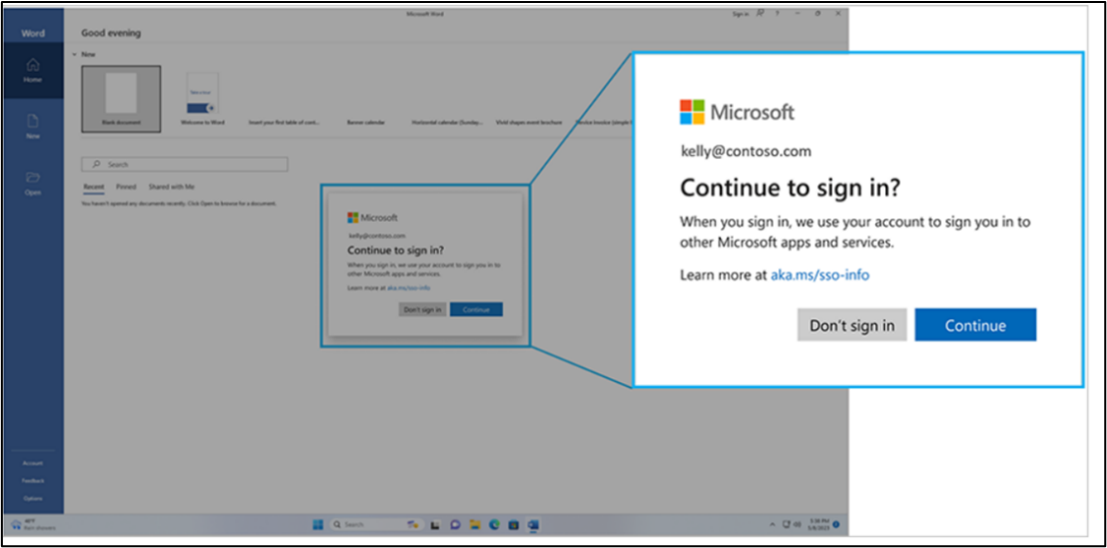

Microsoft is prohibited by Article 5(2) DMA from combining personal data from different (core platform) services. This applies to both Windows and LinkedIn. Microsoft now asks users if they want to synchronise their Microsoft account with Windows so that their data is available on other Windows devices and in Microsoft products where users log in (see also the image below). The information stored in the Microsoft account of an end-user who also uses other Microsoft products is then also available in Windows. This makes it possible for an end-user to restore settings, apps and passwords from another device, as well as synchronise set preferences between devices.

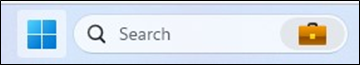

With regard to Windows, Articles 6(3) and 6(4) DMA additionally require that end-users be given the option to change their default settings. Microsoft indicates that end-users will be enabled to remove the Microsoft Edge browser. It also adds new ‘integration points’ for applications in Windows, allowing end-users, for example, to add a search application to the search bar on the Windows taskbar. In this way, end-users can switch from the Bing search engine to another search engine of their choice.

Microsoft will also stop giving recommendations to set Edge as the default browser, including during the configuration process when users first set up or update Windows.

Finally, all (default) apps in Windows can be uninstalled, such as the camera and photo app, Cortana (virtual assistant), Bing’s web search, and Microsoft Edge.

Possible new gatekeepers and CPS: Booking.com, X and ByteDance

Just before Compliance Day, Booking.com and X (formerly Twitter) notified the Commission that they meet the quantitative criteria to be designated as gatekeepers. ByteDance, already designated as a gatekeeper with TikTok as CPS, notified its advertising services, TikTok Ads, to the Commission.

Online intermediation service Booking.com said it expects to meet the DMA’s turnover thresholds from the end of 2023 and thus qualify as a gatekeeper. The reason that Booking did previously not meet the quantitative thresholds is probably mostly due to the (aftermath of the) COVID-19 pandemic, which put a heavy strain on the travel and hotel industry. Of particular relevance to Booking.com would be Article 5(3) DMA, which prohibits it from imposing (narrow or broad) parity clauses on corporate users. This use has already been investigated and fined at national level in recent years, and is now before the CJEU following a preliminary reference from the Amsterdam District Court (see our earlier blog for a further explanation of parity clauses). Regarding X, the most relevant obligation can be found in Article 6(12) DMA pursuant to which it has to apply FRAND criteria for access to its social network.

The Commission now has 45 working days to designate the companies as gatekeepers. If the Commission designates them as gatekeepers, the brand-new gatekeepers will have six months to comply with the obligations under the DMA.

Conclusion

With the substantive obligations for the first six gatekeepers coming into force, the Commission will be primarily occupied with their proposed and/or implemented amendments in the coming months. Especially the adjustments of Meta and Apple have received strong criticism so far. The coming period will show to what extent there is still room for a regulatory dialogue, or if the Commission has shut the door and will initiate enforcement. In addition, the new rules also enable third parties to initiate (private) enforcement against any of the Gatekeepers on the basis of (alleged) infringements of the DMA.