Untangling the DMA in seven questions and answers: a new phase in Big Tech regulation

On 6 September 2023, the European Commission (“Commission”) designated Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, and ByteDance (the parent company of TikTok) as gatekeepers under the Digital Markets Act (“DMA”). The DMA imposes additional obligations on online platforms that enjoy significant economic power and act as an important gateway for business users to reach end users (see also our earlier blog on the DMA). The substantive obligations of the DMA will enter into force in March 2024, subjecting the undertakings designated as ‘gatekeepers’ to a stricter regulatory regime.

In the meantime, Apple, Meta, and ByteDance have already appealed their designation decisions to the General Court of the European Union (“General Court”), and the Commission is conducting market investigations into possible additional designations. ByteDance has also filed an application for the suspension of its designation with the President of the General Court. In this blog, we discuss the scope and obligations of the DMA through seven questions and answers. We also cover recent developments regarding the designations, enforcement issues, and the role of third parties.

- What is the DMA?

- To whom does the DMA apply?

- Which undertakings have been designated as gatekeepers so far?

- What obligations does the DMA impose on gatekeepers?

- When does the obligation to inform the Commission about concentrations apply?

- How is the DMA enforced?

- Does the DMA facilitate private damages claims?

1. What is the DMA?

The DMA is an EU regulation that seeks to safeguard competition on digital markets by ensuring that digital markets remain ‘fair’ and ‘contestable’. The previous years, several online platforms have become so sizeable and powerful that new entrants face significant challenges when competing with these incumbents. Moreover, large online platforms typically possess such a vast and all-encompassing ecosystem that provides them with a significant advantage in reaching end users and enables them to effectively exclude other market participants. Furthermore, the vast amounts of data the gatekeepers generate further reinforce the competitive advantage gatekeepers typically enjoy over their competitors. As a result of the foregoing, innovation and quality in digital markets are diminished as existing competitors are unable to keep up, and new entrants are discouraged from entering the market.

The use of Articles 101 and/or 102 TFEU has not always proven to be effective in tackling these structural issues. Although both the Commission and national competition authorities (“NCAs”) have pursued several investigations in digital markets in recent years (for the Commission, think about the Amazon Buy Box and three investigations into Google), these investigations are often complex and time-consuming. The Commission’s investigations into Apple Pay and Apple’s App Store (music services), launched in 2020, are for example still ongoing. Ex post enforcement action based on Articles 101 and/or 102 TFEU may thus – in the view of the European legislator – in some cases come too late to repair the harm to the competitive playfield. The DMA seeks to close this enforcement gap by providing an ex ante regulatory framework for large online platforms (see also our earlier blog on this subject).

2. To whom does the DMA apply?

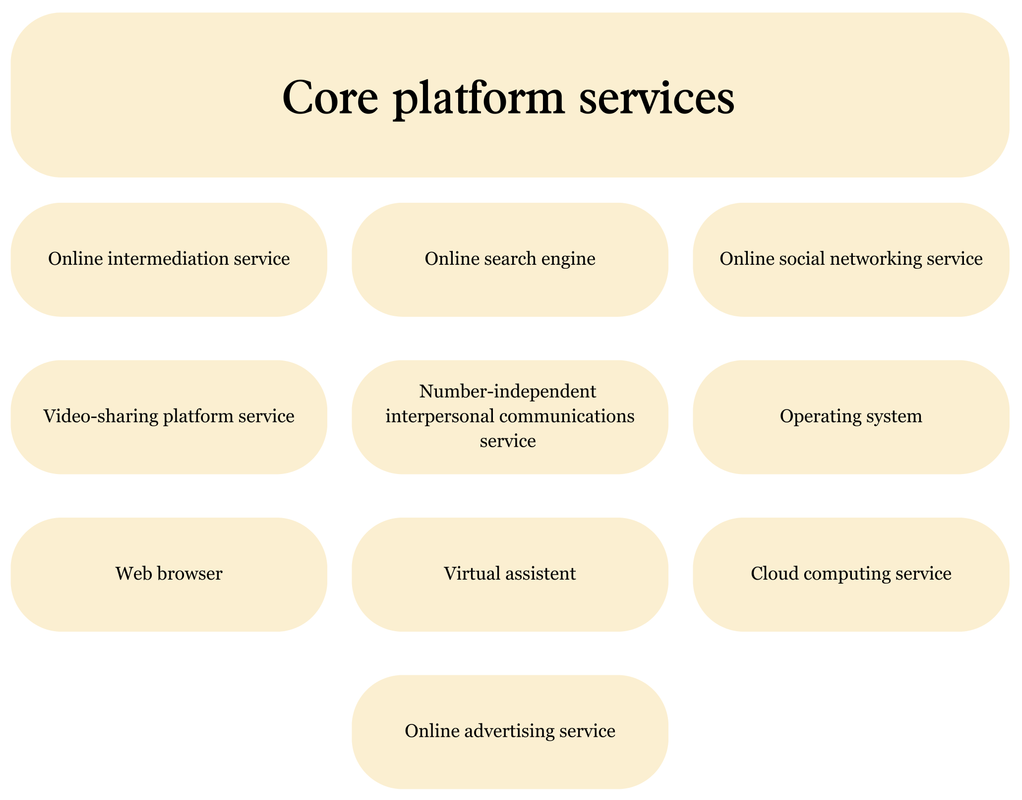

The DMA applies to gatekeepers. A gatekeeper provides one or more so-called core platform services (“CPSs”) The DMA distinguishes the following CPSs:

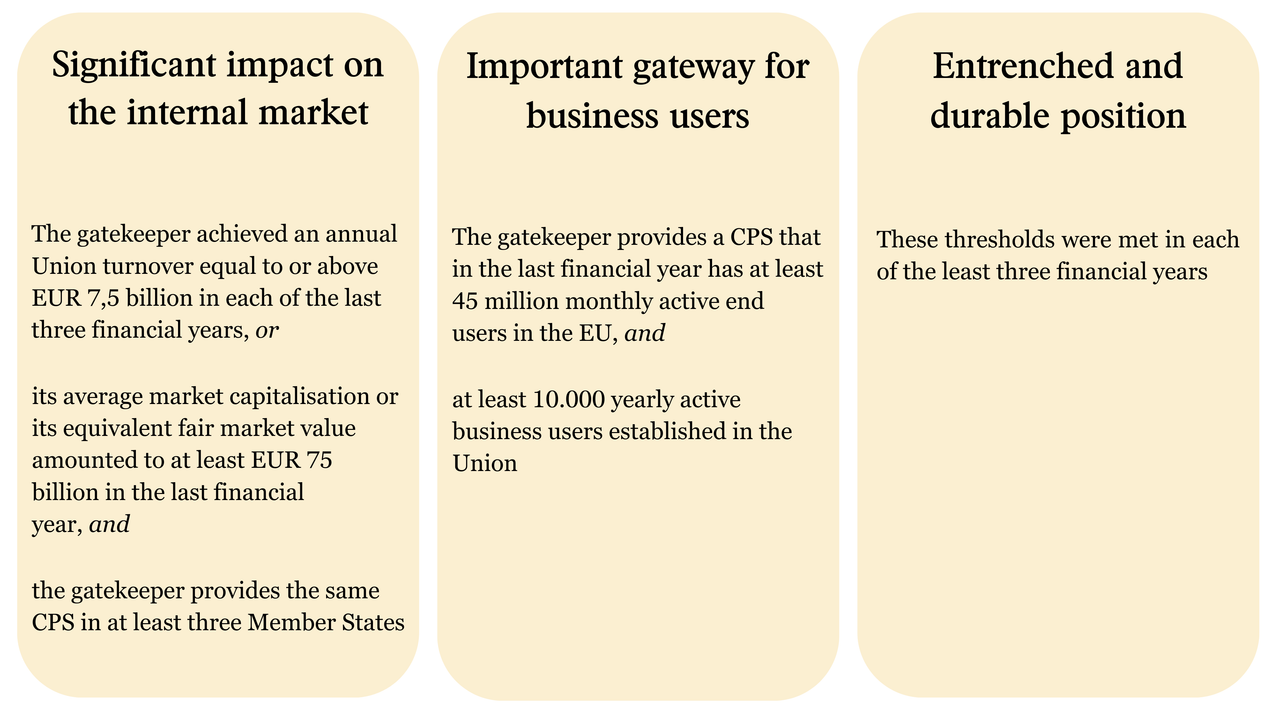

A CPS provider qualifies as a gatekeeper if a number of qualitative requirements are met. A gatekeeper is not necessarily dominant within the meaning of EU competition law. Instead, an undertaking is qualified as a gatekeeper if it (i) has a significant impact on the internal market, (ii) it provides a CPS which is an important gateway for business users to reach end users, and (iii) has or is expected to have an entrenched and durable position. An undertaking is subsequently presumed to satisfy the abovementioned requirements if it meets the following quantitative criteria:

If an undertaking meets the quantitative criteria, it is obliged to notify the Commission within two months after those thresholds are met. Upon notification, undertakings that qualify as gatekeepers can try to rebut this presumption. So far, Alphabet, Microsoft, and Samsung have successfully argued that they should not be designated as gatekeepers as regards their Gmail, Outlook, and Samsung Internet Browser, despite meeting the DMA’s quantitative thresholds. The Commission conceded to the objections and refrained from designating Alphabet, Microsoft and Samsung as gatekeepers with respect to these services.

Where the arguments challenging a designation fall short of outright refuting the designation, but do cast sufficient doubt, the Commission may conduct a market investigation. The Commission is currently conducting investigations in order to establish whether Microsoft Bing, Microsoft Edge, Microsoft Advertising, and Apple’s iMessage ought to be designated under the DMA. In the reverse, the Commission can also designate an undertaking as a gatekeeper on the basis of a market investigation if the undertaking does not meet the DMA’s quantitative thresholds.

A designation by the Commission is not temporally limited. The Commission can, upon request or on its own initiative, reconsider, amend, or repeal a designation if there has been a substantial change in any of the facts underlying the designation, or where it is found that the designation was founded on incomplete, incorrect, or misleading information. The Commission may later also designate new gatekeepers. There is for example already some talk about the potential designation of Booking.com in the near future. So far, Booking eluded the DMA’s quantitative thresholds – in large part due to the COVID-19 pandemic – but is already considered to be a prime candidate for a gatekeeper designation in the media.

3. Which undertakings have been designated as gatekeepers so far?

On 6 September 2023, the Commission designated six undertakings as gatekeepers in respect of twenty-two CPSs. The image below provides an overview.

Source: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/nl/qanda_20_2349

The Commission’s gatekeeper designations could be appealed until 16 November 2023. Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet (Google) expressed that they will not appeal their designations. Apple, ByteDance, and Meta did appeal their designation decisions. In its appeal, ByteDance essentially argues that TikTok does not enjoy an entrenched and durable position and that it does not meet both the DMA’s turnover and capitalisation thresholds (unlike all other gatekeepers so far designated). Meta specifically appealed the designation of ‘Facebook Marketplace’ and ‘Facebook Messenger’. Apple, in its turn, appealed all gatekeeper designations and also filed a complaint against the Commission’s decision to initiate a market investigation into whether Apple’s iMessage should be included in the designation decision. These appeals will probably be decided on next year.

Third parties may join the appeal proceedings before the General Court if they can establish an interest in the General Court’s decision. The ongoing proceedings will reveal whether competitors, customers or other third parties have a sufficient interest already in the stage of the gatekeeper’s designation, or whether this interest only arises in the event of a gatekeeper’s non-compliance with the DMA.

4. What obligations does the DMA impose on gatekeepers?

Articles 5, 6 and 7 of the DMA introduce a wide range of obligations for gatekeepers. Many of the obligations relate to the collection, processing, and combining of (personal) data. Without the express consent of the end user, a gatekeeper is for example prohibited to collect the personal data of end-users using services of third parties for advertising purposes. Additionally, a gatekeeper is prohibited from cross-using personal data generated by a CPS in other services provided separately by the gatekeeper and vice versa. The gatekeeper is furthermore precluded from (re)directing end-users that access a specific service of the gatekeeper into signing on to other services of the gatekeeper with the aim of combining the user’s personal data. Gatekeepers must furthermore provide end users with effective data portability.

The DMA also contains obligations to provide business users, advertisers and publishers insight into the data generated by and/or for them. The gatekeeper may not use the non-public data generated by business users in competition with these users, for example on a downstream market. With regard to advertisers and publishers, there is also an obligation to provide daily information on the ads placed upon their request, free of charge. For online search engines (i.e. for the time being only Google Search), there is an additional obligation to grant third-party search engines, upon their request, access to anonymised ranking, query, click and view data under fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory conditions (also: “FRAND”-conditions).

In addition to these rules on the processing and accessing of data, gatekeepers must abide by many different obligations that, at their core, concern the interaction between different services and the application of fair trading conditions. To this end, the DMA contains both certain do’s – for example, in the context of interoperability of certain hardware and communication services – and don’ts (think of the express prohibition of self-preferencing and the mandatory use of certain identification or (in-app) payment systems). Gatekeepers are also barred from engaging in tying and bundling practices, for example by making the use of one CPS contingent upon the registration or subscription to another. A gatekeeper should enable end users to easily install and uninstall software applications (including third-party app stores) and allow end-users to easily change the default settings. End users should not be (technically) prevented from switching to or additionally using other software applications or services, and should be able to terminate their service with the gatekeeper without undue difficulty.

Furthermore, the gatekeeper should not prevent business users from offering the same products or services to end users through their own direct sales channel and/or third-party services at prices or conditions that are different from those offered through the online intermediation services of the gatekeeper. More generally, the gatekeeper should not prevent business users and end users from going around the gatekeeper and contracting with other parties (e.g. also indirectly by denying access to certain content or features upon doing so). Specifically with regard to app stores, online search engines and online social networking services, the DMA includes the obligation to apply general FRAND access conditions for business users, which should also contain an alternative dispute settlement mechanism.

Finally, to encourage effective enforcement, the DMA explicitly prescribes that the gatekeeper may not restrict or prevent business users and end users from reporting breaches of the DMA or other EU law rules to a competent authority. A full overview of the obligations the DMA imposes can be found in Articles 5 – 7 of the DMA. The designated gatekeepers must bring their operations into compliance with the DMA by March 2024. Gatekeepers must also submit a compliance report to the Commission and establish an independent compliance function.

5. When does the obligation to inform the Commission about concentrations apply?

Another unique feature of the DMA that has so far received rather little attention is the obligation for gatekeepers to inform the Commission of any proposed concentration in the digital sector, regardless of whether the proposed concentration must be notified to the Commission under the EU Merger Regulation (“EUMR”) or to a national competition authority. This duty to inform reflects the increasing emphasis of the Commission on preventing so-called killer acquisitions. It complements the Commission’s use of Article 22 EUMR to examine mergers that do not meet EU and/or national merger thresholds (read more here), and the CJEU’s recent Towercast-judgment, where the CJEU ruled that certain non-notifiable mergers may qualify as an abuse of dominance under Article 102 TFEU.

As the DMA merely introduces a duty to inform the Commission, it does not provide the Commission with additional powers to investigate these concentrations, and hence, to potentially veto them. Upon ‘notification’, the gatekeeper is required to provide a description of the concentration and the activities of the undertakings involved, as well as the annual EU turnover, the value and rationale of the transaction, the number of annual active users and the number of monthly end users. This will allow the Commission to monitor whether new CPSs need to be designated. The DMA also explicitly states that this information could potentially be used for a subsequent Article 22-referral.

6. How is the DMA enforced?

The primary responsibility for enforcement of the DMA lies with the Commission. In addition to the market investigation mentioned above, the DMA provides the Commission with various investigative powers, such as the possibility to request information and conduct inspections (similar to those under Regulation 1/2003). In doing so, the Commission can also impose interim measures. In case of an infringement of the DMA, the Commission, after issuing its preliminary findings, can impose substantial fines and periodic penalty payments, as well as behavioural remedies. These fines can amount to 10% of an undertaking’s annual turnover and may be doubled to up to 20% for repeat offenders. In case of systemic non-compliance (more than three infringement decisions in eight years), the Commission may also impose structural measures (including, for example, a temporary ban on new acquisitions), following a market investigation.

NCAs only play a supporting role in the enforcement of the DMA by monitoring compliance. In the Netherlands, the Digital Markets Regulation Implementation Act (“Implementation Act”) designates the Dutch Competition Authority (Autoriteit Consument en Markt, “ACM”) as the competent national authority responsible for overseeing compliance with the DMA. The ACM possesses various supervisory powers and may initiate investigations into possible breaches of the DMA on its own initiative. Yet ultimately, the ACM reports back to the Commission, and only the Commission can initiate enforcement proceedings under the DMA.

The ACM’s supervisory powers end where the Commission’s investigation begins. It might nevertheless be difficult to establish clear boundaries as these supervisory and investigative powers could overlap. In its recent advice on the Implementation Act, the Dutch Council of State already indicated that the powers of the Commission, the ACM, and the Dutch Data Protection Authority’s (Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens, “AP”) potentially overlap with one another (for example regarding the enforcement of the Platform-to-Business Regulation and the Data Protection Regulation). Also, many obligations from the DMA bear close similarities to (or even: mirror) previous cases that were addressed under ‘regular’ competition law (think of the specific ban on self-preferencing in the DMA following the Google Shopping case). At the same time, the DMA prevents national authorities from taking decisions contrary to a decision adopted by the Commission on the basis of the DMA. In light of these ambiguities, the Dutch Council of State has advised the (Dutch) legislator to complement the explanatory memorandum of the Implementation Act on these points.

Public enforcement of the DMA may also be initiated on the basis of complaints and signals from third parties, including competitors, business users, and end users. Under Article 27 of the DMA, third parties may directly report possible breaches of the DMA to both the competent national authorities and the Commission. The DMA also encourages whistleblowers to report infringements by gatekeepers to the competent authorities. The Commission stresses that whistleblowers can play a crucial role in the enforcement of the DMA as they alert the competent authorities of potential infringements. To encourage employees to ‘blow the whistle’, the Commission has asserted that whistleblowers need to be protected from retaliation. Consequently, the EU Whistleblower Directive is also applicable to the DMA.

7. Does the DMA facilitate private damages claims?

As of now, still little is known about private enforcement of the DMA. On the basis of Article 288 TFEU, all EU Regulations, hence including the DMA, enjoy direct effect throughout the Member States. Individuals can invoke the rights enshrined in an regulation in civil proceedings where the rights granted to the individual are sufficiently clear, precise, and relevant to the individual’s situation. Given that most obligations in the DMA are formulated in a rather specific and precise fashion, it can be assumed that such is the case (also confirmed by the Commission), although Article 6 of the DMA contains obligations that may “be further specified”.

If a third party suffers damages as a result of a gatekeeper’s infringement of the DMA, it may initiate civil proceedings before a national court. Article 39 of the DMA provides for cooperation between the national competition authorities and the Commission in the national application of the DMA. A national court may request the Commission to provide information and issue guidance when applying the DMA in national proceedings. The Commission can also intervene on its own initiative if the coherent application of the DMA so requires. Additionally, Member States must forward to the Commission a copy of any written judgment of national courts deciding on the application of the DMA.

Throughout the legislative process, it has been stressed that the DMA is not a competition law instrument. Also considering the legal basis of the DMA, the procedural guarantees and (material) presumptions that Regulation 1/2003 and the Cartel Damages Directive provide, are inapplicable. The DMA therefore explicitly stipulates that national courts shall not give a decision which runs counter to a decision adopted by the Commission under the DMA. It can thus be inferred that the unlawful conduct (as one of the elements for establishing a tort action under the Dutch Civil Code) is irrefutably established before a national court after a DMA- infringement decision by the Commission (just as it is on the basis of Article 16 of Regulation 1/2003). This will facilitate a follow-on damages claim following a non-compliance decision based on the DMA.

Conclusion

After many years of negotiations, the practical entry into force of the DMA is nearly in sight. Six undertakings have so far been designated as gatekeepers and the first legal proceedings challenging these designations are already pending before the General Court. In the meantime, the Commission is conducting market investigations to determine whether other services provided by these gatekeepers should be designated under the DMA. Given the thin dividing line between the DMA on the one hand and European and national competition rules on the other, national authorities will need to consider how to most effectively shape cooperation among themselves and with the Commission. Third parties such as the gatekeepers’ competitors and customers may also want to prepare for the new rules that are set to apply to their competitors/business partners in March 2024. During the legislative process of the DMA, the legislator strengthened their role in the enforcement of the DMA by providing for an explicit complaint option as well as by implementing several additional rules on how the DMA is to be applied in national civil proceedings. Third parties are therefore expected to play a crucial role in overseeing the enforcement of the DMA.

More questions about the DMA? Please contact one of our competition law specialists.