This is the Competition Flashback Q1 2022 by bureau Brandeis, featuring a selection of the key competition law developments of the past quarter.

Would you like to receive the Competition Flashback news letter of bureau Brandeis by email in the future? That is possible! You will find the registration form here.

Overview Q1 2022

- Enforcement of consumer rights by ACM: principle of legal certainty as a safety net

- Court of Appeal nullifies non-compete clause in cooperation agreement between radiologists due to breach of cartel prohibition

- ACM’s focus areas: digital economy, energy transition & sustainability, housing market

- Further investigation into merger RTL/Talpa by ACM

- The Data Act: European legislative proposal for far-reaching data sharing

- EU General Court annuls billion euro fine for Intel for alleged abuse of dominance

- Court of Justice clarifies the application of ne bis in idem principle in competition law

- Roadshows by the Ministry of Economic Affairs for public company DVI violate the Dutch Act on Government and Free Markets

- Acquisition of Kustomer by Meta approved by European Commission and Bka

- Supermarket chains Coop and Plus may merge under condition of selling several supermarkets

- No compensation for UPS after the European Commission wrongly vetoed the UPS/TNT merger

- European Commission must also pay default interest after (partial) nullity of a fine

Enforcement of consumer rights by ACM: the principle of legal certainty as a safety net

Rotterdam District Court, judgment of 20 January 2022 | ACM, press release of 20 January 2022

Consumer rights in the energy sector have been on the radar of the Authority for Consumers and Markets (“ACM”) for some time now. An interesting development in this context is the judgment of the District Court of Rotterdam of 20 January 2022, concerning a fine imposed by the ACM for the application of unreasonably high cancellation fees to freelancers. According to the ACM, this group should have been regarded as consumers and not as (small) business customers. The court ruled, with due observance of the lex certa principle, that the legislation offers no starting points for the distinction made by the ACM in its guidelines between consumers and (small) business customers. The fine of EUR 1,25 million imposed by the ACM was therefore annulled. The ACM has announced that it will appeal the ruling.

This judgment provides insight into the relationship between policy rules of the ACM and higher legislation. Although the ACM frequently uses guidelines, directives and other soft law in its supervision, the principle of foreseeability requires that ACM’s policy must always be regarded in the light of the intention of the legislator, according to the court.

In this context, reference can also be made to the in-depth investigation into misleading sustainability claims made by two energy suppliers, as published by the ACM on 25 January 2022. Following the publication of the Guidelines on Sustainability Claims, the ACM started a broad investigation in the energy sector in May 2021. The investigation showed that energy suppliers do not sufficiently explain what is the basis of their claims about green energy and sustainability, and fail, for instance, to indicate what percentage of the gas actually consists of green gas or whether it is CO2-compensated gas. The (increasing) supervision of the ACM in the energy sector is thus (again) based on its own policy rules. In the event of judicial review, it might be relevant to assess whether and to what extent the ACM’s guidelines are in accordance with the law.

Court of Appeal nullifies non-compete clause in cooperation agreement between radiologists due to breach of cartel prohibition

Court of Appeal ‘s-Hertogenbosch, judgment of 8 February 2022

On 8 February 2022, the Court of Appeal of ‘s-Hertogenbosch (the “CoA”) handed down a judgment annulling a non-compete clause on the basis of Article 6 of the Dutch Competition Act (“DCA”). The appellant before the CoA is a radiologist working at a hospital operated by Zuyderland. Since 1 January 2015, the appellant transferred his radiology practice to MSB: a cooperation of medical specialists affiliated to Zuyderland. MSB concluded a members’ agreement (the “Agreement”) with the professional company of the appellant, which contains a non-compete clause prohibiting the appellant to perform work (in)directly for healthcare providers competing with MSB without MSB’s permission. In addition, the non-compete clause was to apply for another two years after expiry of the agreement, within a radius of 30 kilometres.

The judgment shows that the radiologist had repeatedly breached the non-compete clause during the term of the agreement. MSB therefore decided to terminate the agreement on 11 April 2018. On appeal, the radiologist argued that the non-compete clause in the agreement was null and void pursuant to Article 6 DCA. Therefore, it could not serve as a ground for termination.

The CoA ruled, first of all, that the non-compete clause is a restriction by object within the meaning of Article 6 DCA. The CoA added that, even if the non-compete clause does not qualify as a restriction by object, it is still a prohibited restriction. It referred to case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”), from which it follows that a non-compete clause for members of a cooperation is generally subject to the cartel prohibition. According to this case law, a non-compete clause may not go beyond what is necessary to ensure the proper functioning of the cooperation. The CoA considered that the non-compete clause at issue did not meet this criterion of necessity, as the proper working of MSB can also be achieved by means of a less far-reaching exclusivity obligation. The CoA therefore upheld the appeal and ruled that the non-compete clause is null and void on the basis of Article 6 DCA. As the other grounds for termination did not justify immediate termination either, the CoA held that MSB did not have a (legitimate) ground for termination.

ACM’s focus areas: digital economy, energy transition & sustainability, housing market

ACM, focus areas 2022-2023, publication of 24 January 2022

The ACM has put three ACM-wide topics on the agenda for the next two years:

- Digital economy: this subject was already on the 2020-2021 agenda and remains topical according to the ACM. The ACM announces, inter alia, that it will take action against online service providers for the use of unfair terms and conditions, decide on access to fixed networks for telecom providers without their own network, and publish guidelines on competition rules for IT-providers in the healthcare sector.

- Energy transition and sustainability: the topic of energy transition was also on the 2020-2021 agenda, but has been expanded to include sustainability. The ACM has announced that it will for example continue to enforce misleading sustainability claims in the energy sector.

- Housing market: The housing market is a new topic on the ACM’s agenda. The ACM will intensify the supervision on rental agencies and realtors and conduct a market study into market power on the municipal-land market.

The coming years, these three topics will receive extra attention from the ACM. This means that we can expect more investigations regarding these topics, and that the ACM will assess tips and complaints in these fields with particular interest.

Further investigation into merger RTL/Talpa by ACM

ACM, decision of 28 January 2022

On 28 January, the ACM decided that a licence is required for the acquisition of Talpa Network by RTL Group. In its Phase I-decision, the ACM specifically foresees the possible creation or strengthening of a dominant position on the markets for (i) the sale of television advertising space, (ii) the production and procurement of audio-visual content, and (iii) the wholesale supply of television channels to distributors such as KPN and VodafoneZiggo.

Due to their strong positions on the market for the provision of television advertising space, RTL and Talpa might increase their prices for advertisers. The ACM even mentions the possibility to leverage their positions on the television advertising market to the radio advertising market (on which Talpa is active with its radio station Q-Music). With regard to the market for wholesale supply of television channels, the ACM also expects that the parties (with a combined market share of 70-80%) could raise prices for distributors and worsen the conditions of, for instance, on-demand services (such as recording television programmes/interactive television). Moreover, the bundling of the parties’ TV activities could place external content producers in a worse bargaining position, and have the result that RTL and Talpa will no longer, or under worse conditions, externally supply the programmes they produce themselves to other broadcasters. According to the ACM, this may come at the expense of the diversity of the television offer. The extensive investigation in the licensing phase will therefore focus on these three – according to the ACM, strongly interrelated – markets.

At first sight, the ACM does not foresee any competition issues in the markets for the procurement of journalistic services, the procurement of facility services and for the provision of retail television services. The ACM for example considers an increase of video on demand services such as Netflix and Disney+, which (may) exert competitive pressure on the retail television services of the parties (RTL XL, Videoland and Kijk), and potentially even on linear television services (live television).

The Data Act: European legislative proposal for far-reaching data sharing

European Commission, legislative proposal of 23 February 2022

On 23 February 2022, the European Commission (“Commission”) presented a new legislative proposal that aims to create a harmonised framework for data sharing by public authorities and companies (such as providers of data-generating products including connected devices and data-sharing services such as cloud/edge computing). The aim of the regulation is to create a level playing field between data holders and re-users of data, and to enable data portability in the event that a user switches to another provider. This way, the Commission seeks to promote data-driven innovation, in line with the Commission’s data strategy to form a single market for data.

The Data Act is a so-called ‘horizontal’ regulation which outlines a general EU-wide framework. The Commission is also considering to adopt more detailed (vertical) regulation in certain specific sectors, such as healthcare and transport.

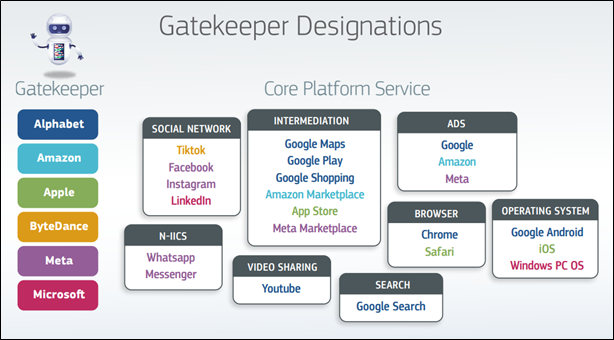

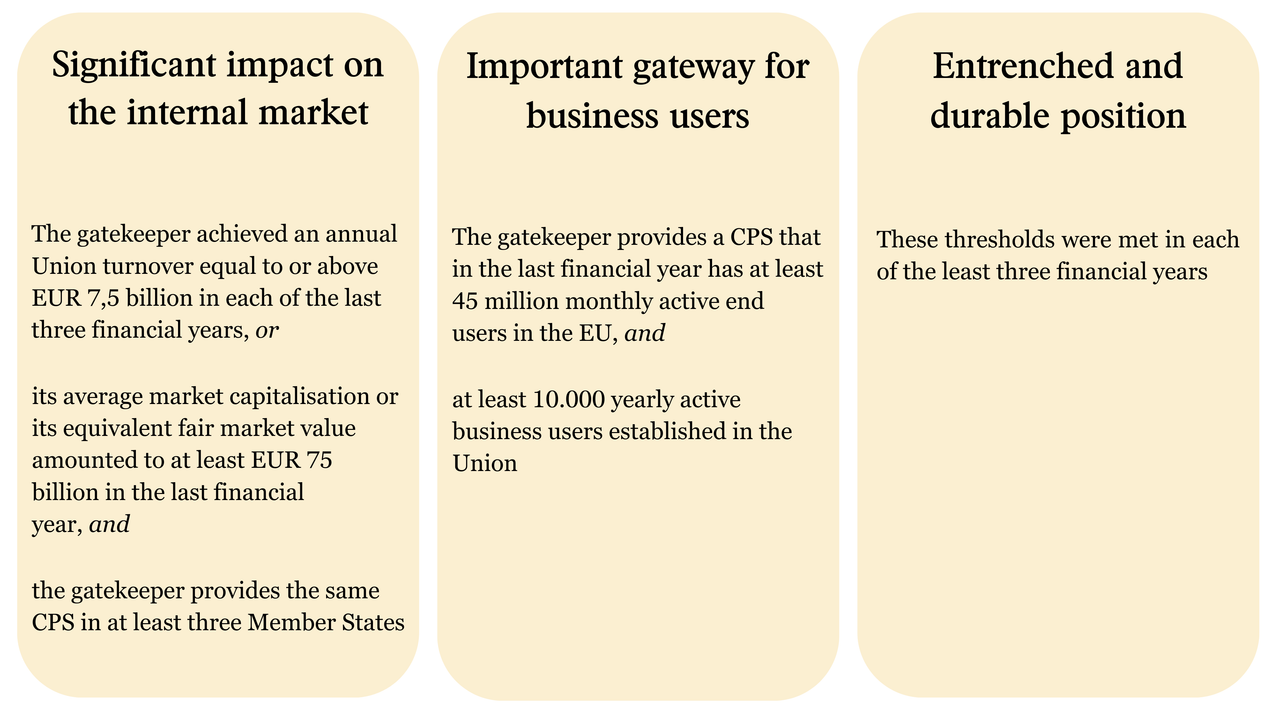

The legislative proposal was publicly consulted last year and will be discussed by the European legislative bodies in the coming period. Given its far-reaching consequences, the Data Act is expected to lead to much political discussion. Criticism has already been voiced by, for example, Big Tech companies that also qualify as gatekeepers under the Digital Markets Act. Under the current proposal, gatekeepers are excluded from receiving data when a customer switches to one of their products.

EU General Court annuls billion euro fine for Intel for alleged abuse of dominance

General Court of the EU, judgment of 26 January 2022

On 26 January 2022, the General Court of the European Union (the “General Court”) partially annulled the Commission’s decision in which it held that chip manufacturer Intel had abused its dominant position. As a consequence, the fine of EUR 1,06 billion imposed on Intel was also annulled. The judgment marks a departure from the per se approach whereby certain conduct is considered inherently anti-competitive. If a dominant company provides (economic) evidence in the administrative procedure that its conduct is not capable of restricting competition, the Commission has to investigate the anti-competitive effects of the conduct.

Background

In 2009, the European Commission fined Intel for abusing its dominant position in the microprocessor market from 2002 to 2007. The Commission found that Intel holds a dominant position in the x86 processor market, with a market share of around 70%. Intel abused this position by (i) offering rebates to four computer manufacturers (Dell, HP, Lenovo and NEC) on the condition that they purchase all or almost all x86 CPUs from Intel, and (ii) making payments to manufacturers that would delay, cancel or restrict the launch or commercialisation of laptops with CPUs of Intel’s rival AMD.

According to the Commission, these so-called loyalty rebates restrict competition by their very nature, so that it is not necessary to analyse the anti-competitive effects. In other words, loyalty rebates are thus considered prohibited per se. The Commission still applied the ‘as-efficient competitor‘ test (“AEC test”) to show that the loyalty rebates made it impossible for equally efficient competitors to compete profitably. Intel appealed against this decision in 2014. Following a rejection of the appeal by the General Court, Intel appealed to the CJEU in 2017. The CJEU subsequently set aside the General Court’s judgment, as the General Court had not examined the Commission’s analysis of the AEC test and Intel’s arguments in relation to that test. The case was referred back to the General Court.

The judgment of the General Court

In the recent judgment, the General Court found that the Commission’s economic analysis was flawed and did not sufficiently demonstrate that Intel’s conduct was capable of producing actual and/or potential anti-competitive effects. Loyalty rebates may be presumed, by their very nature, to potentially have restrictive effects on competition, yet the General Court underlines that this is a rebuttable presumption. According to the General Court, loyalty rebates are therefore not per se illegal. Since Intel brought forward supporting evidence showing that its conduct was not capable of restricting competition and producing foreclosure effects, the Commission should have examined the specific effects of the loyalty rebates. The General Court found that the Commission did not sufficiently demonstrate that the loyalty rebates were capable of having foreclosure effects throughout the relevant period.

As a result, the Commission must repay the fine of EUR 1,06 billion plus an interest of 3,5% (see below). The Commission has announced that it will appeal this judgment.

Court of Justice clarifies the application of ne bis in idem principle in competition law

Court of Justice of the EU, judgments of 22 March 2022 (Nordzucker and Others v. bpost)

On 22 March 2022, the CJEU delivered two interesting judgments concerning the application of the ne bis in idem principle in competition law. In Nordzucker and Others, the CJEU clarified the applicability of the principle where multiple national competition authorities (“NCAs”) investigate a cross-border cartel infringement. After the German Bundeskartellamt (“Bka”) issued cartel fines to German sugar producers for market sharing with effects in both Germany and Austria (partly on the basis of Article 101 TFEU), the Austrian court rejected a subsequent request from the Austrian competition authority to establish a cartel infringement regarding the same undertakings and on the basis of the same facts.

The CJEU ruled that the national court must examine whether the previous decision of the NCA had the purpose of establishing a cartel on the basis of effects on both the German and the Austrian market. If such is the case, the duplication of proceedings cannot be justified under Article 52(1) of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. In order to justify duplication, the subsequent decision must in fact pursue a complementary objective relating to different aspects of the same unlawful conduct. As both the German and the Austrian authorities could (and should) apply Article 101 TFEU, they both pursue the same objective of general interest. The fact that one of the cartel members in the German proceedings participated in a leniency programme does not, according to the CJEU, affect the applicability of the principle.

In case of duplication of infringement decisions based on different types of legislation, pursuing legitimate and distinct objectives, a breach of the ne bis in idem principle could potentially be justified. In bpost, the CJEU ruled that a previous fining decision by the Belgian postal regulator for maintaining a discriminatory tariff system did not, in principle, preclude a subsequent infringement decision by the Belgian Competition Authority (“BMa”) on the basis of Article 102 TFEU, despite the fact that it concerned the same conduct. The CJEU considered that the postal sectoral rules are intended to ensure the liberalisation of the postal sector, whilst the proceedings conducted by the BMa are intended to ensure free competition in the internal market. If there are clear, precise and foreseeable rules, the two procedures have been conducted in a sufficiently coordinated manner are and closely linked in time, and if the overall penalties imposed correspond to the seriousness of the offences committed, a duplication of proceedings would be justified.

Roadshows by the Ministry of Economic Affairs for public company DVI violate the Dutch Act on Government and Free Markets

ACM, decision on objection of 21 December 2021; press release of 24 January 2022

In its decision on objection of 21 December 2021, the ACM found that the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy (“EZK”) violated the Dutch Act on Government and Free Markets (Wet Markt & Overheid, “M&O Act”) by favouring public company Dutch Venture Initiative (“DVI”) with regard to other investment funds. DVI invests in funds that, in turn, invest in innovative, fast-growing SMEs.

The Ministry of EZK tried to interest investors in the DVI by organising road shows, which, according to the ACM, constitutes an infringement of the prohibition on favouring companies within the meaning of Section 25j(1) DCA. The ACM holds that this prohibition is intended to prevent the government from providing competitive advantages to a company for the performance of economic activities in the same way as the prohibition on state aid in Article 107 of the TFEU. For this reason, the ACM assessed whether the attraction of investors to the DVI funds meet the cumulative state aid criteria of Article 107 TFEU, and eventually concludes that it does. Non-financial support can thus also qualify as preferential treatment within the meaning of the M&O Act.

Acquisition of Kustomer by Meta approved by European Commission and Bka

European Commission, press release of 27 January 2022 | Bundeskartellamt, press release of 11 February 2022

On 27 January 2022, the Commission conditionally approved the acquisition of Kustomer by Meta (formerly Facebook). In its in-depth investigation, the Commission envisaged that the acquisition of Kustomer, an innovative player in the market for customer service software applications, could potentially restrict competition in the market for customer service software and customerrelationshipmanagement (“CRM”) support software. Meta’s Whatsapp, Instagram and Messenger are popular messaging channels through which businesses interact with their customers, and therefore constitute important inputs for suppliers of customer service and CRM software. According to the Commission, Meta would, following the acquisition, potentially have the ability as well as the economic incentive to deny or degrade access to the Application Programming Interfaces (“APIs”) for Meta’s messaging channels to software providers competing with Kustomer.

To address these concerns, Meta has offered commitments with a 10-year duration. Meta undertakes to guarantee non-discriminatory access, without charge to its publicly available APIs for its messaging channels to competing customer service (CRM) software providers and new entrants. In addition, Meta offered to make available equivalent improvements and updates of the features or functionalities of its messaging channels to such providers.

The concentration was referred to the Commission under Article 22 of the Merger Regulation (“MR”) by Austria and supported by eight other Member States, including the Netherlands (find our blog on Article 22 MR here). The German Bka decided not to join the referral request and conducted a parallel review of the effects of the concentration. The parties also received approval from the Bka on 11 February 2022.

Supermarket chains Coop and Plus may merge under condition of selling several supermarkets

ACM, decision of 21 December 2021; press release of 6 January 2022

On 21 December 2021, the ACM decided that supermarket chains Plus and Coop may merge under the condition that they divest twelve supermarkets. The ACM has investigated whether the merger will result in higher prices or a less attractive supermarket offer for consumers. According to the ACM, this is not the case on a national level, due to the presence of strong competitors such as Albert Heijn, Jumbo and Lidl.

The ACM also investigated whether consumers have sufficient local supermarkets to choose from. It determined the definition of the local markets on the basis of customers’ willingness to travel to the supermarket by car within 10 minutes. In twelve areas, the ACM foresees that there may be no or limited choice for consumers, with a risk that prices will increase or the range of products and/or quality of service will deteriorate. To address the concerns of the ACM, Coop and Plus will sell their supermarkets in these twelve areas to a competitor.

No compensation for UPS after the European Commission wrongly vetoed the UPS/TNT merger

General Court of the EU, judgment of 23 February 2022 (UPS)

The world’s largest courier company, UPS, will not receive compensation from the Commission for the alleged damage resulting from the failed concentration of the Dutch parcel company TNT, the General Court ruled on 23 February 2022. The Commission decided in 2013 to prohibit the intended concentration between UPS and TNT. Subsequently, UPS decided not to go ahead with the concentration. However, in its decision, the Commission used an econometric model different from the one on which the Commission and UPS had exchanged views during the administrative procedure, without notifying UPS. The ECJ ruled in 2017 that this violated UPS’ rights and subsequently annulled the decision. The ECJ upheld the General Court’s judgment in 2019.

However, TNT had meanwhile been acquired by rival FedEx. This concentration was approved by the Commission on 8 January 2016. UPS therefore claimed damages of over EUR 1,7 billion from the Commission, consisting of inter alia a payment of EUR 200 million to TNT for terminating the proposed concentration, the costs incurred by UPS for being involved in the investigation of FedEx’s takeover of TNT, and the lost profits by not being able to complete the concentration.

According to the General Court, the failure to timely send the definitive version of the econometric model used during the administrative procedure constitutes a sufficiently serious breach of UPS’ rights of defence within the meaning of Article 266 TFEU. However, the General Court holds that there is no direct causal link between that infringement and the alleged damage. The damages stemming from the costs of being involved in the FedEx/TNT merger investigation and the termination clause are not the result of the Commission’s errors, but rather the result from UPS’ free choice to intervene in those proceedings and from a voluntarily agreed upon contractual obligation between UPS and TNT. Finally, there is also no direct causal link between the failure to send the adjusted econometric model and the alleged loss of profit. It cannot be assumed that the concentration would have been approved if the other econometric model had been used. Moreover, UPS itself decided to abandon the concentration after the Commission vetoed it and decided not to make a new offer for TNT to compete with FedEx.

UPS will therefore not be compensated for any of its losses. Although the judgment is understandable from the perspective of the regulators, it creates a high threshold for private parties by expecting them to still actively try to pursue a concentration after it has already been vetoed by the Commission. With this judgment, the General Court introduces a strict standard for successfully claiming damages for an unjustified veto of an intended merger.

European Commission must also pay default interest after (partial) nullity of a fine

General Court of the EU, judgment of 19 February 2022 (Deutsche Telekom)

The General Court ruled on 19 January 2022 that the Commission must repay more than EUR 1,7 million to Deutsche Telekom AG for refusing to pay default interest to the German telecom company. On 15 October 2014, the Commission fined Deutsche Telekom for abusing its dominant position in the Slovak market for broadband internet services. The Commission imposed a fine of approximately EUR 31 million on Deutsche Telekom. By judgment of 13 December 2018, the General Court reduced this fine by more than EUR 12 million. The Commission repaid this amount to Deutsche Telekom on 19 February 2019. Deutsche Telekom also claimed over EUR 1,7 million in default interest from the Commission for the period when it did not have that money at its disposal (i.e. 2014-2019). When the Commission refused to pay the interest, Deutsche Telekom claimed damages before the General Court.

By judgment of 19 January 2022, the General Court upheld that claim. First of all, the General Court concludes that there is indeed a sufficiently serious breach of Article 266 TFEU. The General Court confirmed the CJEU’s ruling in Printeos that Article 266 TFEU imposes an absolute and unconditional obligation to repay, with interest, payments collected in violation of European Union law. Second, the General Court holds that there is a causal link between the damage and the refusal to repay default interest. It points out that an undertaking may expect the Commission to reimburse it for the amount unduly paid, together with default interest, should the fine be annulled or reduced at a later stage.